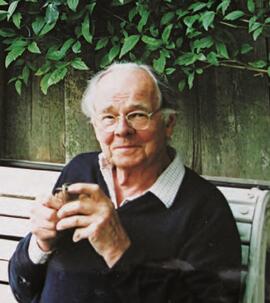

Charles Allix (1921–2015) was a horological expert, researcher, writer, collector and dealer, and a significant contributor to the field of horology. He was the co-author of Carriage Clocks: Their History and Development (1974), and Hobson’s Choice: English Bracket Clock Repeating Work (1982). He also published a series of Malcolm Gardner catalogue pamphlets, Horology and Allied Subjects.

Grahame Brooks is a Freeman of the Goldsmiths Company, Liveryman of the Clockmakers Company, and a freelance contributor to the Horological Journal. He attended evening classes in watch and clock making together with George Daniels at Northampton Polytechnic in Clerkenwell, which later became the National College of Horology.

Eileen Bunt, née Pyatt (b.1926) met Eric Bunt through joint work at the British Geological Survey, probably in the 1950s. The couple were together from the early 1960s, and shared a mutual interest in research and history, frequently visiting the Public Record Office in Chancery Lane, and then later at Kew. She was of invaluable help in Eric’s research centred on the Benjamin Gray daybook, now deposited by the Society with The London Archives, and held at Guildhall Library.

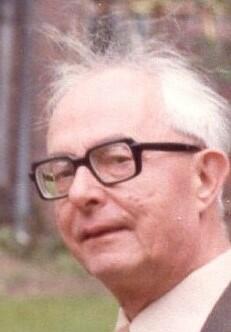

Eric Frederick Bunt (1907–2001) was the Librarian of the Antiquarian Horological Society in 1965–70 and 1974–80.

He was born in Wandsworth to Cyril and Agnes Bunt. His father, Cyril George Edward Bunt (1882–1966) was a respected art educator at the Royal College of Art in London, who had earlier served as the Librarian of the Royal Academy of Arts from 1924 to 1948, a role that perhaps influenced Eric’s career. Cyril was also a keen horologist and was a relatively prolific contributor of articles, particularly to the Watch and Clockmaker between 1928 and 1938 (essentially the whole run of the journal). These articles often focussed on fine pieces held in major museums, and were examples of connoisseurship, rather than the writings of a collector. We can perhaps infer that Eric developed an appreciation for horology from his father.

Eric joined the British Geological Survey as a General Assistant on 14 October 1926 and worked in the library. At some point he was made a Technical Assistant (2nd class) and then on 1 April 1936 moved to the new scale of Assistant III. After the outbreak of the Second World War he became a field assistant doing some magnetic survey work, and later worked for the Water Department, although he continued to do some library work when required. By 1942 he was being referred to in Survey records as Laboratory Assistant – Skilled. Bunt was one of those who supervised the moving of part the Survey’s library and museum collections to University College, Bangor, North Wales to prevent it being damaged by enemy bombing. From 1 January 1946 Eric was classified as an Experimental Officer. He remained working in the library but attended evening classes and did a lot of private reading to improve his knowledge of general geology. In January 1953 he was transferred to the Atomic Energy Division. On 1 January 1954 he was promoted to Senior Experimental Officer. In November 1962 Eric was transferred back to the library to take executive charge of it, on the retirement of the previous postholder. In 1967 he moved from the library and was entrusted with preparing the Survey records which had been selected (with the help of the Public Records Office) for permanent preservation. This meant he played a significant part in the setting up of the Survey’s archives. He retired from the Civil Service in June 1967 but was re-appointed as an unestablished Senior Experimental Officer. In 1969 he temporarily took charge of the library again until a new librarian was appointed. Eric finally retired from the Survey on 30 October 1970.

Eric met Eileen (the donor of this archive) at the British Geological Survey, where she also worked. The two had a strong interest in history and genealogy and were regular researchers at the Public Record Office. Eric also had a strong interest in astronomy, being a member of the British Astronomical Association from 1944 to the mid-1960s. He was a member of their Council 1952–54 and Curator of its Lantern Slides Collection 1951–53.

Eric’s association with the AHS is marked by two distinct contributions. At a practical level he served as the AHS Librarian from 1965 to 1970, being succeeded by Charles Aked, but when Aked wished to step down in 1974, Eric took up the reins again, until 1980.

He published a single though important article in Antiquarian Horology in March 1973, entitled ‘An Eighteenth Century Watchmaker and his Day-Book’. This charted his and Eileen’s painstaking archival detective work in identifying the author of a remarkable daybook to which the AHS Council’s attention had been drawn by Robert Foulkes in 1967. Triangulation of a number of fine details in the daybook with documents in the Public Record Office, particularly Chancery records, as well as parish records, revealed the watchmaker to be Benjamin Gray (Watchmaker-in-Ordinary to George II).

Eileen was clearly important in the research, and his paper notes ‘Few research projects, however small, can be carried out single-handed, and the present minor piece of historical detection is no exception. It is a pleasure therefore to acknowledge the help given by my wife, who has spent many hours patiently copying documents and searching records. Without her encouragement the search might never have been completed.’

Partly on the back of the Gray research, Eric published ‘A chronological directory of Royal Clockmakers 1369–1900’ in Clocks Magazine (in four parts, December 1985 to March 1986) together with Cedric Jagger.

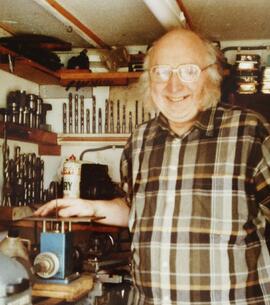

Edward Martin Burgess FBHI (1931–2022) was a horologist and master clockmaker. Born in Kingston upon Hull in Yorkshire, he became a leading expert on his fellow Yorkshireman John Harrison and his scientific approach to precision timekeeping. Burgess was one of the members of The Harrison Research Group, founded in 1977 by a group of horological scholars. He set about making two clocks according to the Group’s understanding of Harrison’s specification. The first of these clocks, known as the Gurney Clock, was on public display in Norwich from 1984 until 2015. The second, its sister clock (Clock B) was finished in 2014 in the workshops of Charles Frodsham & Co. and was subsequently successfully trialled at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich.

Martin Burgess was also the creator of monumental ‘sculptural clocks’, one of which – the Schroder Clock commissioned in 1969 – was recognised in the Guinness Book of Records as having the largest clock wheel in existence.

In honour of his horological achievements, Martin Burgess was awarded the British Horological Institute’s Barrett Medal in 1988 and the Clockmakers’ Company Derek Pratt Prize in 2014.

He lived in Boreham, Essex, with his wife Eleanor.

Roger F. Carrington (1948–2005) was a horological researcher, specialising in Liverpool watchmaking. He was the author of important articles published in Antiquarian Horology: "Thomas Yates of Preston, Watchmaker & Experimentalist' (1975) and “Pierre Frederic Ingold and the British Watch and Clockmaking Company” (1978). He also undertook painstaking research at Guildhall Library into watchmakers and clockmakers in insurance records, and was a collector of unusual horological items which he sourced at antique markets. Although publication plans for his proposed books were cut short by his untimely death, he left behind a wealth of research papers and manuscripts in various stages of completion.

John W. Castle (d.1962) was a member of the AHS and a contributor to Antiquarian Horology in its early years. In the 1950s, he undertook research for a book about famous clocks of Europe. He lived in Pinhoe near Exeter, Devon, and in Hambridge, Langport, Somerset, England.

Percy G. Dawson (1905–1992) was an antiquarian and clock-case maker based in London, the author of The Iden Clock Collection (Antique Collectors Club, 1987) and co-author of Early English Clocks: A discussion of domestic clocks up to the beginning of the eighteenth century (Antique Collectors Club, 1994). He was a member of the British Horological Institute, a founding member of the Antiquarian Horological Society, and the editor of Antiquarian Horology from 1953 till 1959. In 1994 the AHS introduced the Percy Dawson Medal for the best article by a new author submitted to Antiquarian Horology, to pay tribute to the memory of its first editor.

Henry Draisey (1896–1975) was a clockmaker and Fellow of the British Horological Institute from 1953/54. He began his clockmaking career in 1920 with Niehus Bros of 39-40 Bridge Street in Bristol, ‘manufacturers of English church, turret and factory clocks’, both locally and for international markets. From a 1931 reference letter, we know that he ‘undertook the work of supervising and estimating for inside and outside work including the making and repairs of turret clocks. Mr Niehus considered him a first-class workman and had complete confidence in him.’

Presumably while working at Niehus, Henry assisted an amateur maker, Mr Mosely (an engineer from Bristol) to make a longcase clock designed to demonstrate Grimthorpe’s gravity escapement. Mosely was 82 when the project was started in 1923, and it took three years to complete. Draisey would encounter the clock again later in life.

Mr Niehus’s poor health led to the closure of the firm and Henry’s redundancy in late 1931. He then worked on his own as a clockmaker through the Great Depression.

From 30 June 1947, he worked for Pleasance and Harper, also in Bristol, a firm that described him in a reference of May 1951 as ‘perfectly honest and a thoroughly experienced clockmaker, able to undertake complicated and difficult work’. While working for the firm, Ernest G. Harper, chair of Pleasance and Harper, submitted an application form to the BHI on Henry’s behalf in January 1949, commenting on his significant skills (‘he can make any part of any size for any type of clock’), and the fact his own workshop staff begged him to employ Henry ‘for what they can learn from him’. Harper suggested he should be considered for the award of a Fellowship of the Institute, as he ‘would pass with flying colours any exam either practical or theoretical’. Henry duly transferred from CMBHI to FBHI in 1952 (Horological Journal, November 1952). While still at Pleasance and Harper, the Moseley clock was cleaned by the firm, and transferred to the Mansion House in Bristol.

Finally, Henry worked for Llewellin’s Machine Company, working on timekeeping equipment in all areas, including watchman’s clocks and time recorders, though he clearly had a long independent career working in clocks.

Jeremy Lancelotte Evans (1951–2026) was a horologist and expert on seventeenth and eighteenth-century clocks. He was regarded as the foremost authority on the life and work of Thomas Tompion, having built that knowledge over more than three decades working in the Clocks and Watches department of the British Museum. He was the author of Thomas Tompion at the Dial and Three Crowns (AHS, 2006) and co-author, with Jonathan Carter and Ben Wright, of Thomas Tompion: 300 Years (Water Lane, 2013). He also wrote a number of articles for Antiquarian Horology as well as the Dictionary of National Biography entries for George Graham, Daniel Quare and Thomas Tompion.

Jeremy was born in Hitchin and grew up in Pirton, attending Pirton Primary School, and then Bessemer School for Boys. His father was the North Hertfordshire librarian and curator of local museums at Hitchin and Stevenage, and his mother collected nineteenth-century American shelf clocks. Jeremy was an avid collector with wide interests by the age of nine, and he bought his first clocks in local junk shops in his early teens, beginning a lifelong fascination with horology.

After a short spell working for Woolworths in 1966–67, he joined Pyman Jewellers in Letchworth, staying from 1967 to 1970, where he worked on clock, watch and jewellery repairs. The firm paid for him to attend Hackney Technical Collage, Dalston Lane, on a day-release basis for three years, where he took a first class in his finals.

A short spell at Thwaites & Reed in 1969–70 led to joining the British Museum in July 1971. He worked in the Clocks and Watches Department alongside other well-known figures over time, such as Beresford Hutchinson, John Leopold, and latterly David Thompson, before retiring in December 2005. His horological career was marked by a strong research focus, and he was always a phenomenal compiler of lists, whether of serial numbers, dates, newspaper references, and much more.

His family moved to the house in Pirton in 1953 which Jeremy and his sisters retained, and where he lived with a long line of faithful dogs as companions, the last of which was Eddy, a Welsh terrier.

Mildred Florence Frederiksen (1889–1966) was a collector of information on horological curiosities, and a regular reader and occasional letter writer to Horological Journal.

She was born Mildred Florence Faulkner in January 1889 to William Henry Faulkner and Emily Ebsworth Faulkner (née Honeybone), both schoolteachers. She was named Mildred Florence from the name on a gravestone in the churchyard of St. Mary-le-More, Wallingford, next to which her mother lived and had been brought up. Though Emily knew nothing about the person buried there, the name had taken her fancy as a child. At the time of Mildred’s birth, the family lived in the district of Benhilton near Sutton, Surrey, to the south of London.

In July 1934, aged 45, Mildred married Laurits (sometimes Laurids) Christian Frederiksen, a Danish-born tailor living in Bayswater, London, who had naturalized a couple of months earlier. Soon afterwards, until at least the outbreak of the Second World War, the couple lived in a flat in Powis Square, Notting Hill.

In 1935 and 1936, Mildred achieved modest fame to readers of some British newspapers owing to her appearance in advertisements for McDougall’s self-raising flour, in which, as “Mrs. Frederiksen”, she offered recipes and described the pastry-making that formed part of her domestic life at Powis Square.

By 1955, the couple had moved to Greenfield Place, Weston-super-Mare. That year, she started to create what was to become a series of scrapbooks entitled “Clock Miscellany,” a project that would continue until her death. It is possible that this was prompted by her finding that she was descended from the clockmaker Richard Honeybone of Fairford, Gloucestershire – she tracked down numerous clocks made by him and gave an address on the subject to family and friends in May 1955. Mildred’s horological interests certainly became very broad, as her scrapbooks demonstrate. In a letter to the Horological Journal in May 1959, she noted, “I collect interesting items about clocks and clockmakers, and in fact anything bearing on the subject.” Her friends would send her horology-related postcards, pictures, and articles. Postcards sent by friends on holiday showing floral clocks around the world became a particular collecting theme.

Mildred Florence Frederiksen died at the age of 77 in December 1966, at a hospital in Wells, Somerset. Her husband died eight years later, in March 1975, at an old people’s home in Weston-super-Mare.

Lily Hudson (1920–2023) was the first secretary of the Antiquarian Horological Society. She worked as a personal assistant at an RAF training centre during the Second World War and in 1950 joined the British Horological Institute to work as an assistant to Major Cowen, the BHI Secretary. She became instrumental in organising BHI trips to France and Switzerland in 1950 and 1951. Her meticulous recordkeeping was crucial to the eventual formation of the Antiquarian Horological Society in 1953. After leaving the AHS in 1956, she remained in touch and took part in the Society’s milestone celebrations as an honoured guest.

Michael George Hurst (1924–2017) was a horological historian and restorer, a founder member of the Antiquarian Horological Society (1953), a member of its Council from 1968 to 2010, and the author of several articles published in Antiquarian Horology.

He received a BSc degree in engineering from Imperial College and served in RAF as a pupil pilot in 1943–45. After the war, he worked as assistant engineer and eventually joined Hurst, Peirce and Malcolm, a family firm of Consulting Civil and Structural Engineers, who were involved in the rebuilding of Mercers’ Hall, Brewers’ Hall and Grocers’ Hall. He became senior partner in 1969.

Michael developed an interest in antiquarian horology, especially in styles, mechanisms, original methods of clockmaking, restoration and reconstruction of early English and Continental pieces. He was particularly interested in the work of various significant seventeenth–century makers, notably Edward East and Ahasuerus Fromanteel. In 1964, he assisted in the organisation of the “Collectors’ Pieces” exhibition celebrating the tenth anniversary of the AHS. He also served for many years as an assessor/examiner on the Clocks Course at West Dean College. In 1970, Michael was admitted as a Freeman of the Clockmakers’ Company, taking the Livery in 1973, and serving as Steward in 1981. In 2003, the year of the fiftieth anniversary of the AHS, he was elected a Fellow for exceptional services to the Society. In 2010, he retired from the AHS Council after just over 40 years’ service, being elected a Vice President.

He was accompanied in the pursuit of these interests by his wife Jacqueline (née Moore), whom he married in 1964. Together they developed a small horological collection and library. The Hursts lived in Mill Hill, London.

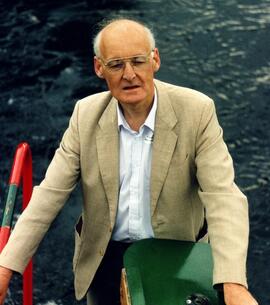

Beresford Hutchinson (1936–2006) was a distinguished horologist whose career spanned practical restoration, museum curation, scholarship, and generous mentorship within the horological community. Born in Hastings, Sussex, on 19 December 1936, his fascination with clocks began in childhood. His father repaired clocks as a hobby, and by the age of six Beresford had already taken apart and reassembled his first clock. As a teenager he developed his skills further by assisting local watchmakers and antique dealers.

He attended Hastings Grammar School before going on to Queen Mary College, London, to study botany. His studies were interrupted by National Service in the RAF, with postings including Omaha, Nebraska. After demobilisation he returned to horology, working from 1961 to 1964 with the respected restorer Percy Dawson in London, while studying at Hackney Technical College and gaining his Fellowship of the British Horological Institute.

In 1964 he joined the British Museum as an assistant in the horological collections, becoming research assistant in charge of the department following the death of Philip Coole. His contributions included advising on major exhibitions, notably the innovative permanent gallery opened in 1976, and important acquisitions such as the Buschman clock with remontoir, and the Godman regulator. He was known for his encyclopaedic knowledge of the collection and for his patient, supportive encouragement of students and visiting researchers.

In 1979 he moved to the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, where he served for a decade as Curator of Horology. There he oversaw significant acquisitions, including the major Foulkes bequest, and contributed to publications on chronometers and scientific instruments. His personal passion extended across the history and technology of timekeeping, from turret clocks to radio-controlled watches and mass-produced nineteenth-century examples.

Alongside his curatorial responsibilities, he played an active role in the horological community. He served the Antiquarian Horological Society as a Council member, supported the British Horological Institute and the Clockmakers’ Company, taught evening classes, lectured widely, and advised dioceses, collectors, and museums. He published Orologi Antichi, a book on antique clocks in Italian, in 1982 and contributed papers, lectures and consultations throughout his career.

After retiring in 1990, he returned to hands-on conservation and became a familiar figure at the Brunel Clock Fair, selling items from his own collection and offering advice with characteristic humour. He continued to write, consult, and restore clocks almost to the end of his life.

Known variously as Hutch, Berry, and Beresford, depending on the period of his career, he was admired not only as a leading authority across the breadth of horology, but as a kind, modest and witty colleague. His sudden death from a heart attack at home in Charlton on 10 April 2006, shortly before his seventieth birthday, was widely felt as a great loss to the world of horological scholarship and friendship.

Chris McKay (1949–2023) was a horologist and a renowned expert on turret clocks. He joined the Antiquarian Horological Society and its Turret Clock Group in 1969, later becoming its Treasurer, Secretary, Vice–Chairman and Chairman. He was also a member of the British Horological Institute and its Director in 2007–9, becoming a Fellow in 2013. Chris was also a bell ringer and in the 1960s and 1970s was affiliated with the University of Sussex Guild of Change Ringers.

Chris worked briefly in the civil service in Barry, Wales, fitting electronic equipment to an oceanographic research vessel. He later joined the commercial electronics industry and became involved in technical sales and marketing. He was involved, with Malcolm Loveday, in the research into the history of the Big Ben clock, to help place its 1976 failure in its historical context. He organised “The Great Salisbury Clock Trial” in 1993, organised the first Turret Clock Forum at the BHI headquarters in 2008, and established Turret Clock Taster days. He consulted and worked on clocks in the UK and beyond, including Argentina, Australia, Canada, Ghana and Italy.

He authored a number of horological books, articles and letters, including The Turret Clock Keeper’s Handbook (revised edition 2013), The Maintenance, Repair, Restoration, Conservation and Preservation of Turret Clocks (2016), Big Ben: The Great Clock and the Bells at the Palace of Westminster (2010), and Longitude's Legacy: James Harrison of Hull 1792–1875 (2015). He also issued a number of facsimiles of clockmakers’ catalogues and Bailey’s Illustrated and Useful Inventions.

Chris McKay lived in Hinton Martell, Dorset, UK, and for many years chaired the Dorset Clock Society and acted as the Salisbury Diocese Clocks Adviser.

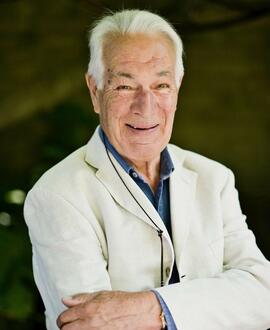

Milo Mighell (pronounced Mile; b.1931), officially John Mighell, is an expert on English, Continental and American clocks and author of a number of articles on clock collecting. He brought the attention of clock collectors around the world to previously neglected areas of horology, such as tavern clocks and Vienna regulators.

Milo had been working for 26 years for an international mining corporation until 1968, when his friend, journalist Doug Blain, came up with an idea of opening a clock shop. This became Strike One (Islington) Limited.

Robert Henry Astin Miles (1926–2019), known as Bob Miles, is best known as a founder member of the AHS Electrical Horology Group in 1970, and as the author of the definitive work Synchronome: Masters of Electrical Timekeeping (2011, 2nd edition 2019).

Born in Hertfordshire and educated at Cambridge and London Universities, Bob Miles worked for almost forty years on the development, measurement and production techniques of quartz crystals used in communications. He first became interested in horology in the early fifties and joined the Antiquarian Horological Society in 1955, soon becoming the photographer of its social events, especially the early foreign trips, and its press officer. Later, in 1988, Bob became the first Chairman of its East Anglian Section, and then its Secretary.

He translated two important horological resources into English: the Bulle Practical Manual and a collection of Brillié catalogues and manuals. His interest in pocket watches was soon supplanted by that in electrical horology, leading to the formation of the Electrical Horology Group, and eventually, to the publication of his seminal work on the Synchronome company.

In 2005, Bob entered into a civil partnership with his long-term partner Frank. In 1972 he was a co-founder of the Cambridge Group for Homosexual Equality, a cause close to his heart.

Arthur Mitchell (1929–2018) specialised in electrical horology. He joined the Antiquarian Horological Society in 1966 and upon the foundation of its Electrical Horology Group in 1970 became its first Secretary, a position he held until 1995, when he was elected an honorary member of the Society. During that time, he organised meetings and visits to collections and exhibitions, and published annual technical papers. In 1976-–77 he was a member of the organising committee for the “Electrifying Time” Exhibition held at the Science Museum. In 1997 he became the Society’s Librarian, remaining in post until November 2011. He was responsible for reviving the library, working on both cataloguing and new acquisitions. He was also a member of the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors in the USA from 1972.

He was employed by the Ministry of Defence as a draughtsman, working on various aspects of machinery control and installation procedures for warships and submarines.

Anthony James Moore (1929–2013), otherwise known as Jim Moore, was born 30 May 1929 in Cheveley, near Newmarket, Suffolk. He met his wife, Beryl, while they were both students at Nottingham University where he read Mathematics. He followed this with an MA in Education, completed in 1951. After university he enlisted in the RAF and was appointed to a National Service Commission as a Pilot Officer in the Education Branch at the end of 1951. He married Beryl in late 1952, and they moved to the West Country, to RAF Locking, Weston-Super-Mare, while he served in the RAF teaching mathematics. A succession of teaching posts followed, leading to a headmastership at Chew Valley Secondary School in 1962, where he stayed for two decades, transforming it from a secondary modern to a comprehensive, while pupil numbers grew from 300 to more than 1000.

He took early retirement in 1983, to expand his knowledge and love of antiques. Specialising in the restoration and sale of antique clocks, especially those of Somerset and Bristol origin, he was well known as a keen collector, dealer and valuer at auction houses and clock fairs. He was also a keen gardener and very fond of roses.

In 1991, having discovered that little was known about the local clockmakers, he set out to find what he could about them and developed a passion for research into them, expecting to list two or three hundred names and to complete the work in twelve months. In fact, enough material was discovered to fill three books, Bilbie and the Chew Valley Clockmakers (with Roy Rice and Ernest Hucker 1995), The Clockmakers of Somerset (1998) and its companion volume The Clockmakers of Bristol (1999). Altogether, over the nine years while researching and writing the books, the names and details of over three thousand craftsmen associated with clock and watchmaking in Bristol, Bath and Somerset were recorded, and more than three thousand of their clocks. The names and dates were taken from original seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth-century written records, including parish records, church accounts, deeds, and wills, from both private sources and county record offices.

After thirty years of a full and active retirement, Jim Moore died 8 June 2013, aged 84. Beryl died the following year on 25 November 2104. Both cremated, their ashes are buried together at Felton Church, near Lulsgate, Avon. They left four daughters and five grandchildren.

Lewis Stafford Northcote (d.1977) was an early member of the Antiquarian Horological Society, who made considerable contribution to antiquarian horology. Together with the late Dr Beeson, he helped advance the study of turret clocks by discovering, recording and classifying clocks of importance, not least the significant clock at Idbury, with its two-plane escapement. He was also a superb draughtsman and many horological works published in the 1960s and 1970s bear evidence of his craftsmanship.

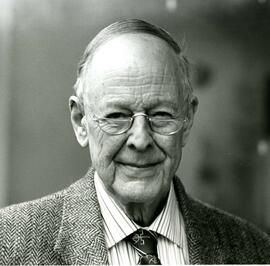

Tom Robinson (1915–1999) was Chairman of the Antiquarian Horological Society from 1985 to 1991. He became a member of the Society in 1956 and contributed actively to its affairs and to its publications for forty years. He served as Editor of Antiquarian Horology in 1962–68 and 1975–78. He was elected to the Council in 1963 and served on the Libraries and Publications Committees for a number of years. During his Chairmanship of the Society he instigated its first specialist sections: he was the first Chairman of the Southern Section and the co-founder and second Chairman of the Turret Clock Group. In 1996 he was elected a Vice President of the Society.

Tom was a qualified Chartered Electrical Engineer, working for the Post Office at the time when it was the only supplier of telecommunications services in the UK. He masterminded the setting up of two of the company's training schools, of which he was the Director: Charles House in Kensington and the school at Kew, from which he retired in 1975.

His interest in horology started at school, when he repaired clocks for friends in his spare time. His later interests focused on the on the seventeenth century, but his broad knowledge and expertise in both clock making and cabinet making were well demonstrated by his major published work, The Longcase Clock (1981, 2nd edition 1995). His unpublished works include the internal catalogues of the remarkable collection of clocks at the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge.

Tom was a member of the Furniture History Society from its inception in 1964, of the Conservation Committee of the Council for the Care of Churches, and Chairman of its sub-committee on Clocks Conservation. He also advised the dioceses of Chichester and Guildford on their clocks. He continued with his research right up to his death, his latest interest being lacquer-cased clocks.

Tom shared his horological interests with his wife Eileen (d.2015), to whom he was married for forty-five years and who was a Life Member of the AHS.

Dr Frederick George Alan Shenton (1928–2003) was a medical doctor and horologist, with a thirty-five year career as a general practitioner (family doctor). His interest in horology led him to carry out research and documentation of clocks, watches and tools, as well as developing practical restoration skills. He was a member of the British Horological Institute, the Antiquarian Horological Society (which he joined in 1964), and the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors of America. In 1970, he became a founder member of the AHS Electrical Horology Group and acted as its chairman in 1975–79. He was a contributor to the major electrical horology exhibition, “Electrifying Time”, held at the Science Museum, London, from October 1976 to April 1977. A prolific author, he wrote several technical papers for the Group and contributed articles and book reviews for Antiquarian Horology. For some time he was a consultant to the publishers of the Horological Journal. In 1977 he co-authored, with his wife Rita, The Price Guide to Collectable Clocks 1840–1940, a reference book which has since seen three editions. In 1979, he published another successful book, The Eureka Clock. His last major work was Pocket Watches of the 19th and 20th Century, published in 1995.

To commemorate Dr Shenton’s interest in the nineteenth- and eighteenth century horology, and to encourage research and publication in the more recent horological subjects, in 2004 the AHS set up the Dr Alan Shenton Award. It is made for the best Antiquarian Horology article on timekeeping in the period since 1840.

The Shentons lived in Twickenham, London.

Rita Kathleen Shenton, née Chapman (1935–2004) was the Chairman of the Antiquarian Horological Society and the founder and owner of Rita Shenton Books.

Her interest in horology, shared with her husband Alan, started flourishing around 1971, when after years of working for an insurance company and raising three children, she was finally able to pursue it. In 1974 she established Rita Shenton Books, a business in second-hand trade of horological literature, which arose from the need to reduce the surplus of items in the Shentons’ ever-growing personal library. In 1976, the business expanded into publishing. That year, Rita wrote a short biography of Christopher Pinchbeck, Christopher Pinchbeck and His Family, which was followed in 1979 by Alan’s The Eureka Clock. In the meantime, they co-authored The Price Guide to Collectable Clocks 1840–1940, which became a classic reference book on the subject. Rita was also a prolific writer of articles for magazines and journals, especially Clocks, to which he became an important contributor right from its first issue in 1977, and where she published a regular column of news from the book trade.

Rita joined the Antiquarian Horological Society in 1972 and soon became involved in the organisation of its foreign tours, visiting museums and private collections and making them a great success. In 1978 she joined the Society’s Publication Committee, was involved in its programmes and lectures, and in 1986 became a full member of the Council. Ten years later she became the sixth Chairman of the AHS, the first woman to hold the post, and in 1998 she was elected a Liveryman of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers. As a member of the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors, Rita was awarded a Gold Medal in 2000, 'For an Outstanding Contribution to the Field of Horology and Dedication to the Association.' She was also a prime mover in the organisation and preparations for the AHS fiftieth anniversary celebrations at Oxford in 2003. After Alan’s death later in the same year she set up the Alan Shenton Memorial Fund both to commemorate his name and to further the cause of horology of the period 1840 to 1940. Shortly before her own death in 2004 she was unanimously elected Vice President of the AHS.

Strike One (Islington) Limited, founded in 1968 at 1A Camden Passage, Islington, was one of London’s best-known specialist dealers in antique clocks, whose stock also included watches, barometers, music boxes and books. It was owned and operated by Milo Mighell, and founded with his friend and business partner, the journalist Doug Blaine. Strike One also specialised in the restoration of antique clocks and barometers. At the height of its success in the 1970s, the premises at 1A Camden Passage occupied three floors, with a showroom and a workshop, where Ron Rose was employed with two others repairing and restoring the clocks for the shop. Its main clientele consisted of private buyers, mostly resident and visiting Americans and English couples looking to furnish their houses with antique clocks. In the 1980s, as horological dealership became more competitive, Milo moved to 51 Camden Passage nearby, to smaller premises without a workshop as Ron Rose started working from home. Around 1992 Milo decided to follow suit, leave the Camden Passage premises and trade from home in Balcombe Street, Marylebone. Around 2004 Strike One was taken over by Rafferty & Walwyn Fine Antique Clocks of 79 Kensington Church Street, London.

Mary Frances Tennant (1927–2018), née Goddard, was a New-York-born painted dial restorer and conservator, and the author of two books on the subject: Longcase Painted Dials: Their History and Restoration (1995) and The Art of the Painted Clock Dial (2009).

Frances specialised in art and dance during her time at the Brearley School in Manhattan, and emigrated to England after her marriage in 1949 to David Alan Tennant, a British Navy officer. They eventually settled at The Stone House in Rossett, Wales, where they set up their studios after David retrained as a horologist, and Frances began applying her artistic skills to the painting of enamels and the restoration of painted clock dials. Using innovative restoration techniques, she always started the restoration process with a record of photographs when the dial was received, and concluded with images of the completely restored dial. Frances contributed to an exhibition on dials held at Prescot Museum and lectured widely on these subjects.

Philip Thornton (1901–1975), born in Great Haywood, Stafford, was a horologist and a manufacturer of milling cutters for clock wheels and pinions. He was also an accomplished clock maker, designer and engraver. In the 1930s and 1940s he was engaged mainly in clock making and restoration, becoming an expert at the repeating mechanisms used by Tompion and his contemporaries. He made striking longcase clocks in Knibb’s style, and after the Second World War, in collaboration with Frodsham & Company, he made hump back carriage clocks with perpetual calendar in the style of Breguet, the first of which was presented to HM Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother. His last creation was a Roman numeral striking clock, intended to be the first of a new series.

Alan Treherne (1938–2025) was a Vice-President of the Antiquarian Horological Society and its former Council member. He authored several horological exhibition catalogues, including Nantwich Clockmakers: Catalogue of Clocks and Watches exhibited at Nantwich Museum (1970) and The Massey Family: Catalogue of an Exhibition at the Museum, Newcastle-under-Lyme (1977).

E. John Tyler (1920–2012) was the author of European Clocks (1968) and Black Forest Clocks (1977).

Francis Wadsworth (1935–2007) was the Antiquarian Horological Society’s Technical Enquiry Officer from 1965 to 1999, and the chairman of its Publication Committee. He studied horology at the Northampton Polytechnic’s National College of Horology and joined the Antiquarian Horological Society in 1954 as one of his youngest members. His career began at Smiths Clocks in Glasgow, where he designed alarm clocks and a timer, the latter of which went into production. In the early 1960s he moved to Cambridge to join W. G. Pye (later Pye Unicam), where he worked on the design of a scientific analysis equipment. Around that time, he started organising small meetings of local horologists, which later evolved into the East Anglian section of the AHS.

Francis was principally interested in watches. His paper, “A History of Repeating Watches'”, published in Antiquarian Horology from September 1965 to June 1966, became a definitive study of the subject and was later reprinted as a booklet. Another of his particular interests was the history of the Lancashire Watch Company. In his later years, he carried out a study of post-war clock manufacture in Britain.

As the Technical Enquiry Officer at the AHS for over thirty years, he answered enquiries from the members drawing on his encyclopaedic knowledge and his substantial private library. He promoted the role as the AHS as a publisher of horological books as the Chairman of its Publications Committee, and took an active role in their production. With his wife Christine, he hosted annual horological lunches at their home. As keen collectors on interesting horological items sourced from markets and fairs, they had a stand at the Brunel Clock Fairs for a number of years.

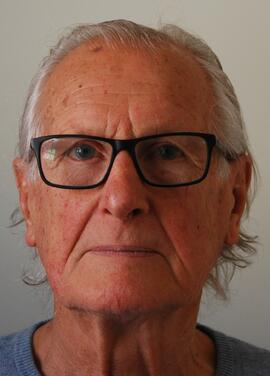

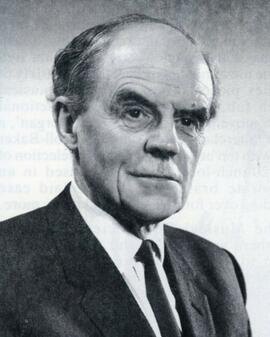

Dr Frank Alan Burnett Ward (1905–1990) was a founder member of the Antiquarian Horological Society, its Treasurer, Programme Secretary, Vice-President, and the organiser of Continental tours for the Society.

Born in Stockport, Cheshire, he was educated at Highgate School, London, and Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, where he read physics and undertook research in nuclear physics with Lord Rutherford at Cavendish Laboratory, gaining a PhD (Cantab). His main career, which spanned nearly forty years starting in 1931, was at the Science Museum, London. As Keeper in the Department of Physics, Dr Ward was involved in managing the Time Measurement Collection, from sundials to quartz clocks. He also organised two major exhibitions there: ’The British Clockmaker's Heritage' (1952) and, in conjunction with the AHS, 'Collectors' Pieces, Clocks and Watches' (1964). During the Second World War he was seconded to the Air Ministry (Meteorological Office) and was later commissioned in the RAFVR (Meteorological Branch).

After his retirement in 1970, Dr Ward catalogued the British Museum's collection of European scientific instruments, as well as the clock and watch collections at the Victoria and Albert Museum and Waddesdon Manor. Between 1973 and 1985, he published fifteen articles in Antiquarian Horology.